George “Poochie” Ross’s history of Richmond jazz is missing. His 295-page dissertation is not.

Virginia’s institutions of higher education were not fully open to Black student enrollment until 1972. So when Ross—a bassoonist and saxophonist—began pursuing his Master of Music degree in 1961, he went north to Eastman, following in the footsteps of Richmond-born conductors Leon Thompson and Paul Freeman. Today the powers that be are concerned about the deleterious effects of DEI programs. I share this concern. Richmond could have been a sort of southern Boston, Cleveland, or Chicago in terms of art music prominence. But Discrimination, Exclusion, and Institutionalized racism resulted in a “brain drain” as many of the city’s greatest talents went elsewhere to flourish.

Ross’s Eastman years came in two stints. After earning his Master’s, Ross briefly returned to teach in Richmond Public Schools (RPS) between 1967-1969. His own CV notes during that time Ross “composed over twenty works for symphony orchestra” and “sixteen of his compositions for marching band have been published.” He became a member of ASCAP in 1969. Although I’ve yet to locate these specific works for student orchestra, the numbers track with Ross’s overall prolific output as a composer and arranger. My experience as a public school orchestra director tells me they’re probably sitting in a very dusty file cabinet in a Richmond band room right now just waiting to be rediscovered.

Ross’s second Eastman stint was from 1970 to 1975. At 1975’s Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival, he was unanimously voted Outstanding Instrumentalist and Best Composer-Arranger (Big Band Category) for his “Reflections.” The judges were Dan Morgenstern, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Muhal Richard Abrams, Hubert Laws, Jack DeJohnette, Sonny Rollins, and Chuck Rainey. Ross’s lifelong friend and RPS classmate Lonnie Liston Smith had served on the festival panel the previous year.

In July 1975, he would earn his Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Education advised by Paul Lehman. Dr. Lehman later became president of the Music Educator’s National Conference during the “back to basics” years of the 1980s when school music programs were threatened with cuts nationwide. “What a pleasure to be reminded of George Ross!”, Lehman told me in 2022:

You have jogged my memory. I remember him as a very intelligent young man with a ready smile and an engaging sense of humor. It was obvious that he would have a bright future. I also remember that we shared a background as bassoonists.

Ross’s DMA dissertation is a remarkable piece of work.

At first, it looks quite dry and “academic,” in the pejorative sense of the word. The study’s two stated objectives are (1) to supply practical performance material for the student performer and (2) to provide information of varying types that can lead to broader appreciation of the particular compositions. Chapter 1—the bulk of the work—includes Ross’s transcriptions of duets by composers from Guillaume Dufay to J. S. Bach to Arnold Schoenberg, all carefully sourced, graded, and annotated. (Sue Cressman and Joanne Swartz assisted Ross in typing the manuscript.)

Let’s recall, though, that here is a symphony orchestra bassoonist who was tight with Sonny Stitt and Paul Gonsalves. Chapter 2 is where things get syncopated. “Jazz Duets for Two Bassoons” begins with a thoughtful introduction, list of jazz-influenced compositions (by the likes of Milhaud, Gershwin, Stravinsky, Bernstein, and others), and various definitions of jazz from interviews Ross conducted with Bernard Garfield, Alec Wilder, David Baker, Warren Benson, and Rayburn Wright. Here’s Baker’s take:

Jazz is essentially improvisation.

It is music coming out of the black aesthetic.

Its central focus is rhythm.

Jazz is the maximization of personalized expression.

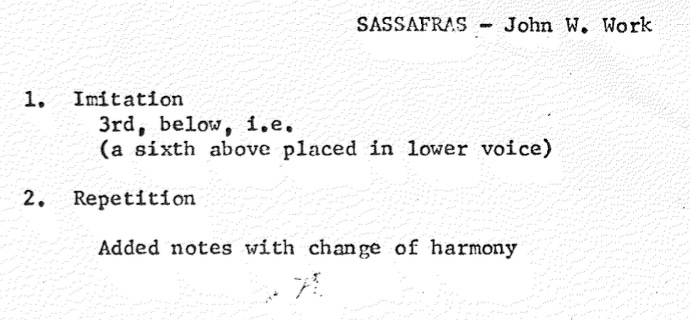

Ross’s personalized expression of music education was informed by his Virginia State College music theory professor, the composer and pianist Undine Smith Moore. Moore’s unpublished theory textbook A Recorded Supplement to Studies in Traditional Harmony advanced the novel practice of “studying the structure and organization of musical compositions through listening and analysis of Music literature,” including works by Black composers such as William Grant Still and John W. Work. (The B in “Black composers” is capitalized in Moore’s original introduction, circa 1951-1957.)

Ross advances this concept by adding his own original takes on the jazz tradition. Furthermore, he makes his project’s anti-racist educational agenda explicit:

There exists a large amount of literature pertaining to the history and significance of jazz. One of the sources of difficulty is that often scholars have omitted the names and contributions of many black musicians who were involved with this music. Because jazz has traditionally been closely associated with black musicians, this omission has been particularly unfortunate. This deficiency gradually is being filled by various Ph.D. and D.M.A. dissertations and numerous new books dealing with the multitude of diverse aspects of jazz.

His duets are based upon careful study of “how the religious hymn, work song, slave song, spiritual, ragtime, blues, dixieland, swing, bebop, third-stream, avant-garde, and the ‘free-thing’ styles are related to one another and fit together in the background of jazz.” This includes capsule histories and a thorough scholarly consideration of the aesthetics of Scott Joplin, Black gospel music, Paul Gonsalves, New Orleans jazz, Harry Carney, Charlie Parker, and John Coltrane. The eight duets are:

“Raggin’ with Joplin”

“Jesus My Lord”

“Blues for Paul”

“Dixie in Richmond”

“Swing for Harry”

“Bebop for Parker”

“Rocking Chair Rock”

“Tranetracks”

Ross’s pedagogical magnum opus resolves with a terse conclusion that speaks volumes:

The diversity of the sample represented in the dissertation compels the student to confront a broad range of problems, both technical and expressive, that will prepare him in turn to be a versatile, responsible, and well-informed musician.

Diversity, confrontation, responsibility—talk about gradus ad Parnassum! For what is essentially a book of bassoon etudes, these are pretty lofty expectations. His teacher Undine Moore’s words bear repeating: “If any teacher succeeded in exhausting the technical musical elements and organization of the blues, the jazzes, gospel, or the related musical ideas…who could complain of shallowness and lack of worth in blues study?” These two unpublished pedagogical works are key nodes in Virginia’s long and rich history of Black perspectives in music education, situated halfway between Hampton Institute vocal music professor R. Nathaniel Dett’s 1917 “The Emancipation of Negro Music” and Virginia Commonwealth University’s contemporary Journal of Hip Hop Studies.

As artists, educators, and administrators grapple with multiple recently-declared fronts in the American culture war, it pays to remember the value of anti-racist arts education and what we lose without it.

Can you imagine if every college music professor in America or woodwind section in regional symphony orchestras could shred smooth jazz-hard bop crossover LIKE THIS (from Ross’s 1981 LP Dedications)?

Can you imagine if elementary school music rooms universally included portraits of Scott Joplin, Mahalia Jackson, and Paul Gonsalves alongside busts of Beethoven?

Can you imagine if there were no “girl” or “boy” instruments? White or Black instruments? Just instruments with diverse, global legacies you sampled to find your own voice?

Imagination is still a free country and American music “an annotated historical anthology” of free-thinkers like George Ross.

I forgot to mention that Ross doesn't title his composition "Dixie in Richmond" or use the term "Dixieland" uncritically. He writes: "The term often referred to as Dixieland was used to differentiate between jazz played by white and black musicians. Several serious studies of jazz discuss varying viewpoints in the origin and validity of some of the connotations associated with this word. The student investigating this term may refer to such books as those by Schuller, Stearns, Larousse, Feather, Harvard Dictionary, Hodier, and Hentoff."

I am going to have to spend some time with this important piece, but I do want to cite one disagreement re the statement:

"Jazz is essentially improvisation."

I believe the late great historian Larry Gushee, in his book on The Creole Band, has show this to be a misconception. There is a lot of early jazz that is more rhythmic paraphrase and displacement than improvisation in the accepted, defined sense. Jazz in this way is as much a matter of tonality, timbre, time and, well, attitude of expression. We might argue that some of this is improvisation, but I think, in its early years, the musical evolution of jazz is more complicated than that; look at James Reese Europe, whose earliest recordings swing but do not use improvisation. I would argue that it qualifies as jazz, as does the work of some other early players, including those who "planned" their solos ahead of time.